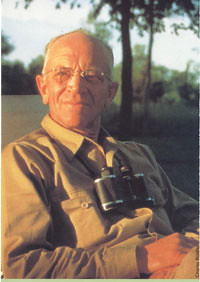

Over his 40-year career as a forester, scientist, teacher, and writer, Aldo Leopold brought a greater understanding of our relationship with the natural world at a time when the technological advances of the 20th century increasingly shut people off from their surroundings.

Jan. 11 marked the 125th anniversary of Aldo Leopold’s birth and provides us with an opportunity to reflect on his contribution to forest conservation and ecosystem management. Leopold’s ability to communicate, by untangling the complex world around us into stories that we could easily understand and internalize, distinguishes his contribution to conservation.

Leopold is most widely known for his collection of essays Sand County Almanac and Sketches Here and There originally published in 1949.

The fact that Leopold is still recognized as one of conservation’s leaders serves as testimony to the clarity, credibility, and depth of experience in his work.

Leopold based his writings upon extensive experience working the land. He spent the first twenty years of his career employed by the Forest Service, first in the southwest and later at the Forest Products Laboratory in Madison, Wis. Through hard won experience he gained an understanding of the myriad ways that elements of forest ecosystems interacted and the wisdom in forest conservation.

“When the pioneer hewed a path for progress through the American wilderness, there was bred into the American people the idea that civilization and forests were two mutually exclusive propositions…A stump was our symbol of progress,” he wrote in 1918 from New Mexico, where he worked on the Gila National Forest. “We have since learned, with some pains, that extensive forests are not only compatible with civilization, but absolutely essential to its highest development.”

Leopold’s early recognition of keeping and restoring biological diversity and ecological processes became central to his evolution of thought on the environment.

What Aldo Leopold teaches us today more than ever is the benefit that comes from slowing down and taking the time to listen to nature. In today’s world, being quiet is a valuable commodity; taking time to stop and listen for those minute details outdoors that weave a tapestry of stories all around us is a rewarding experience if we but stop and pay attention.

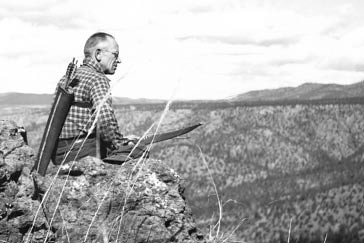

Leopold could read a landscape, just as well as we can read his prose, but he did not try to keep this knowledge to himself; instead he tirelessly worked on communicating the knowledge he had accumulated to those around him.

Imparting this understanding became his way to serve the land, his motive always to promote conservation of natural resources as demonstrated in his oft quoted statement, “We love (and make intelligent use of) what we have learned to understand.”

As we remember the anniversary of Leopold’s birth, let us celebrate his unabashed enthusiasm and persistence in protecting and improving this land we all share.