What are the macro trends in food production and policy? In this blog, USDA Senior Economist Anne Effland gives an overview of how consumers are shaping the way food is grown and how USDA is supporting the evolving food system. Read more in the article Effland co-authored with Carolyn Dimitri in the journal Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems.

What’s the central idea of your recent article in Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems?

In our recent article, my coauthor Carolyn Dimitri (New York University) and I revisit work we published with Neil Conklin a decade ago while we were both at USDA’s Economic Research Service (ERS). That work examined the transformation of U.S. agriculture and agricultural policy during the 20th century. Similar to that earlier work, we focus on trends in farm structure, technology, and policy, but we have moved the story forward from 2000, and have placed more attention on the increasing influence of consumer preferences on the U.S. food system, including the growth of organic agriculture and local and regional food markets.

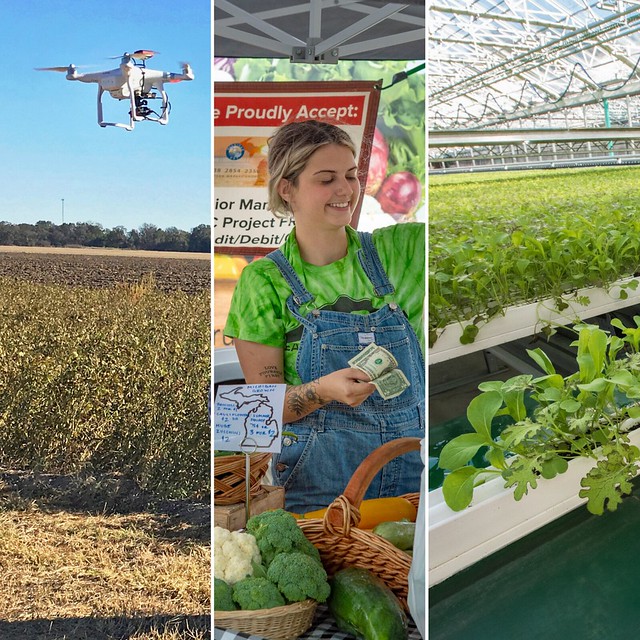

Drawing on a wealth of recent studies, including a number by researchers at ERS, we highlight the continuing consolidation and specialization in U.S. farming, influenced in part by new technologies that continue to increase the productivity of U.S. farmers. Some of those technologies include biotechnology, precision agriculture and robotics, and indoor farming systems, all heavily influenced by applications of advances in digital information technologies to agriculture. We also highlight the increasing focus on risk management in U.S. farm policy, as well as the effect of the growing consumer interest in farm and food policy on the range and types of programs added to the Farm Bill that assist alternative agricultural production and marketing approaches.

In the article, you talk about the ways that new technologies – such as precision agriculture - spur greater productivity yields. How has precision ag affected large-scale and smaller-scale farming?

Precision agriculture uses information technology and equipment (such as tractors equipped with GPS and sensors) to optimize productivity. This approach has the potential to increase returns by helping producers match inputs to the specific needs of crops. Controlling input use can reduce costs for producers while also reducing nutrient runoff and chemical use. While larger farms are more likely to be able to make the investments needed for adoption, research suggests that smaller scale farms can also increase operating profits by adopting precision agriculture technologies. Use of precision agriculture continues to be concentrated in field crops and the most commonly adopted technologies are GPS guidance systems, yield and soil monitors/mapping, and variable rate input application technologies. Producers of high-value specialty crops (such as fruits, vegetables, tree nuts, and horticulture and nursery crops) have begun to adopt precision irrigation systems that control delivery of water, nutrients, and pesticides. Robotics technologies like auto-steering tractors and drones, have developed alongside precision agriculture to facilitate both data collection and precision input applications, Adoption of these advanced technologies remains relatively slow, likely due to cost and to the learning curve involved in making the best use of precision data to improve operations. Data privacy issues may also be of concern, as farmers often have limited control of how companies providing precision agriculture services use collected data.

Tell us more about the new “food movement” -- how did it start, what is driving it, and why is it important?

What has come to be known as the food movement grew from concerns among consumers developing in the late 20th century about the environmental and social costs of the large-scale efficiency-oriented agricultural and food system. The 20th century food system produced abundant food at low cost and allowed most of the U.S. labor force to work outside agriculture. The system supported an urban society in which most people are food consumers rather than producers and in which consumers have become increasingly distant from the agricultural source of their food.

The food movement thus reflects in many respects a reengagement by consumers with how their food is produced and marketed. It encompasses a wide array of concerns, but those concerns can be roughly divided between a focus on equitable access to nutritious, affordable, fresh foods produced using environmentally responsible practices, and a focus on healthy and safe food products and the footprint of large-scale agriculture on environmental quality, landscapes, and communities. These concerns have begun to influence food sourcing by supermarkets and large restaurant corporations, in turn forcing changes in agricultural production practices, as well as creating increased demand for fruits, nuts, and vegetables and local and regional food markets. They have also led to an increasing number of small-scale farms oriented to supplying food grown using alternative, often organic, production methods to local and regional markets.

How do new technologies contribute to the emerging food movement?

New technologies contribute to different aspects of the food movement. While some alternative farming advocates, including many organic producers, decline to use new technologies, not all have taken that approach. For example, while biotechnologies such as gene editing remain controversial in the food movement, biotechnology methods to develop lab-grown meats has gained some traction as an alternative to animal agriculture. Some precision technologies—robotic milking, for example—appear to be scale-neutral, meaning their adoption can be equally profitable for both small- and large-scale operations. In addition, the same field-level precision agriculture technologies used in conventional agriculture are used for organic grain production.

One of the focuses of the emerging food movement is production of food in the locality or region where it will be consumed. Indoor agriculture, including greenhouse operations and vertical farming, makes use of precision agriculture technologies for delivering water, nutrients, and pest management, in some cases without use of soil (as in hydroponic, aeroponic, and aquaponic agriculture). Such approaches have contributed to the viability of urban farming, a means of making locally grown food available to city residents, and to farming practices that may reduce the land needed for agricultural production in the future.

How has the food movement affected policy?

As a broad combination of concerns, the food movement has had an influence on the range of programs encompassed in the Farm Bill. Increasing consumer attention to the environmental effects of agricultural production has contributed to expansion of conservation program, especially those supporting organic and other low-input farming practices. Loan and technical assistance programs that facilitate entry of beginning farmers and support small-scale production have in part been the result of food movement advocacy. Policies to support organic farming, such as cost-share for the certification process and crop insurance policies that recognize higher value of organic crops, also reflect the influence of consumer preferences and food movement interests, as do programs to expand access to fresh produce in schools and nutrition programs.

How has the food movement influenced marketing?

Perhaps the greatest example of change in the marketplace resulting from the food movement or changing consumer preferences is the rapid growth in availability of organic products—organic food sales increased five-fold from 2002 to 2015 following establishment of the USDA organic certification program, and the number of certified organic farms recently increased 11 percent in a single year, from 2015 and 2016. Also increasing have been new marketing channels for local and regional foods. While farmers markets and other direct-to-consumer sales such as community-supported agriculture remain core to local and regional food trends, accounting for 35 percent of sales in 2015 (according to USDA’s Local Foods Marketing Practices survey), new strategies like regional food hubs that aggregate, store, process and market locally grown foods and direct sales to local food retailers, wholesalers, and institutions like schools and colleges have created new ways for local food to reach more consumers.

Despite the recent rapid growth in these sectors and markets, however, they remain a relatively small share of the U.S. food system. Organic products make up only about 5 percent of U.S. food sales, and direct-marketed sales to consumers, retailers, wholesalers, and institutions make up less than 1 percent of U.S. food sales.

What changes do you see in the structure of farming in the United States?

21st century structural change continues the trend toward consolidation—we are seeing fewer, larger farms measured by both acres and in gross sales. While the simple average farm size in acres using Census of Agriculture data suggests that farm size has become fairly stable, that result masks the falling number of farms in the mid-size range, as more smaller farms balance the growing number of larger farms. The number of farms exceeding 1,000 acres and annual sales over $500,000 and the number of farms with fewer than 50 acres and annual sales less than $10,000 have both increased. The number of farms with acreage and gross sales between those two categories continues to fall. And according to ERS, the small, though growing, share of farms with annual gross sales greater than $1 million accounted for about half of agricultural production in 2015

Farm support programs have moved over the last 30 years from supporting prices to providing tools for producers to manage their risks. These changes mark a trend toward a business risk management approach in production agriculture. Increased private research and development in seed and animal breeding technologies and precision agriculture and robotics, for example, as well as private initiatives in the food system value chain that specify production practices may be pressing a reorientation of commercial agriculture towards a greater reliance on private services and standards. At the same time, growing consumer interest in local and regional production, processing, and distribution by smaller-scale participants in the food system may be creating a niche opportunity to provide those consumers with access and attributes not available through the large-scale conventional food system.

How these trends will develop in the future remains to be seen, of course. In the meantime, the current suite of Farm Bill programs offers support both to traditional agricultural producers and to those serving these growing niche alternatives.